OSHA’s New Maximum Penalty Structure: Are Roofing Contractors Ready?

If there was ever a time for an employer to think about consequences of one’s actions on the job, it’s now.

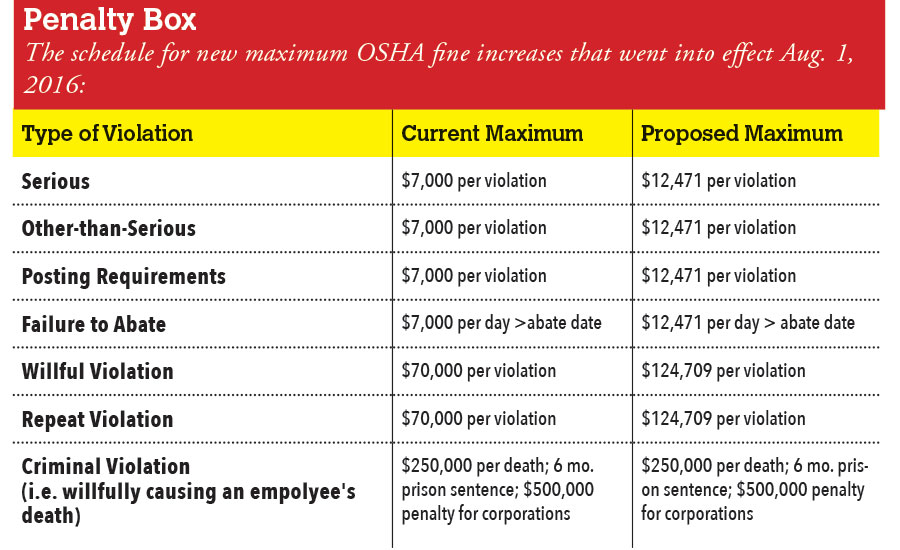

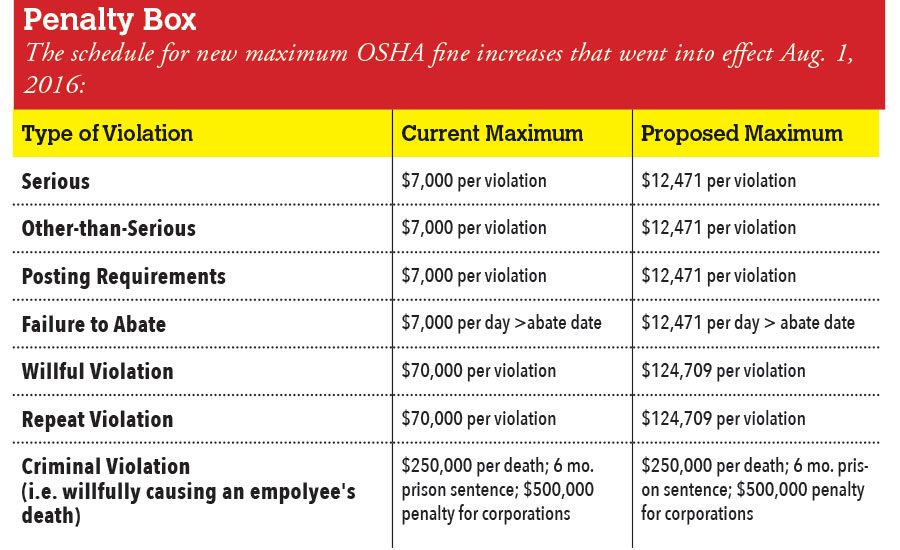

On Aug. 1, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) implemented its new maximum penalty system, adjusted to the current U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) Consumer Price Index (CPI). For the past 26 years, OSHA’s penalty limits remained comparable to the 1990 CPI, but Dr. David Michaels, assistant secretary of labor for OSHA, repeatedly petitioned congress in committee hearings for higher penalties, declaring, “Employers can be fined more for mistreating cattle on federal lands than for allowing an employee fatality!”

Last November, members of the Republican-controlled 114th Congress granted him his wish and proposed the Federal Civil Penalties Inflation Adjustment Act. The amendment was a compromise in a long contested, bipartisan budget agreement to keep the federal government funded and to not default on the growing national debt. The Final Rule from OSHA was published in the Federal Register on July 1 — when the congressional subcommittee finally arrived at an increase adjusted for inflation capped at 150 percent of existing penalties with a “recommended” 78 percent maximum allowed increase in penalties. These will affect: OSHA; the Employee Benefits Security Administration; the Mine Safety and Health Administration; as well as the worker’s compensation program.

On Aug. 1, OSHA also issued the latest revision to its Field Operations Manual reflecting the rate changes. Consistent with prior regulations, extenuating circumstances including the size of a business and the employer’s “good-faith” effort to abate problems may continue to impact OSHA penalty reductions. Those 27 states and U.S. territories with self-administered occupational safety and health programs will be required to adopt the same maximum penalty policy as OSHA states.

When I think about it, the price for a gallon of milk rose nearly 68 percent in the same time period. In 1990, I could buy almost two bags of groceries for the cost of less than one today. It’s probably no wonder that the maximum cost an employer may be assessed by OSHA for an alleged violation should rise as well. Keep in mind that the assessment of a penalty may not, in every case, equal the maximum allowed by federal law. Also remember that any payment of an OSHA penalty is submitted directly to the U.S. Treasury Department and never to OSHA. Since 1970, OSHA has operated on an annual budget issued from the Treasury, having been assessed during the previous year’s congressional term.

It was surprising to many in the safety and health field that this increase didn’t come earlier. For instance, many in the field thought appropriate changes would come around the new millennium. While fines issued by OSHA are often settled for 50 percent of the maximum penalty allowed, they’re primarily based on the size of the business inspected, history of previous violations, and the employer’s demonstration of “good faith” to abate or mitigate the hazards.

They’re also notoriously based on the compliance officer’s assessment of the gravity of the standard violation. This subjective evaluation of any violation is based on:

1) the probability of an accident on the jobsite involving employees; and compounded by

2) the potential severity of an accident potentially affecting those employees exposed.

According to the OSHA Act, an employer may contest either the citation issued or the proposed penalty assessed before the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission. He or she must notify the OSHA area director in writing within 15 days of the citation’s issue date, otherwise it can’t be legally contested. Likewise, an employee has the right to contest the employer’s abatement period in writing, postmarked within 15 working days of the posting of any citation.

All postings must be:

1) near each site of the alleged violation;

2) placed so it’s readily seen by any affected employees and read in a language in which they are fluent; and

3) left posted for three days minimum or until the violation is corrected.

If contested by an employee, a notice of contest shall be posted beside the original OSHA citation, until the area director rules on the contest issues.

If there was ever a time for an employer to think about the consequences of one’s action (or inaction) on the job, it’s now. For decades, OSHA fines were looked upon by many as simply one of the “costs of doing business.” One industrial contractor with whom I was contracted to safety train and consult called me into his office to tell me my services were no longer required.

His bookkeeper had informed him that morning that my fees were in excess of any of his OSHA fines. Investment in his employee safety and health training and OSHA standard compliance apparently was no longer economically viable compared to the cost of his citations over three years. Since then, he’s learned the unfortunate consequence of generating a higher Experience Modification Rate (EMR).

His company’s high EMR (>1.5) categorized it in a high-rate assigned risk pool with his state insurance carrier. In addition, it limited his ability to have his bid accepted by many large contracts, as well as placing his firm “on notice” from the state’s Worker’s Compensation Insurance Board that the policy may be suspended. Suddenly, his view of the “cost of doing business” changed dramatically.

Time will certainly tell us exactly how this increased penalty schedule will effect business trends. Will compliance with OSHA/MSHA standards rule the day, rather than focusing on the corporate profit before employee’s safety? After all, according to the OSH Act of 1970, financial penalties were always designed to coerce American businesses, as the standards were to educate them.

Until the day comes when every American employer willingly assumes his or her general duty to protect every employee’s wellbeing for the duration of their employment, only OSHA penalties will have any impact on the worker’s federal right to a safe and healthy workplace. After all, without teeth, a dog’s bite would be little more than a nuisance during most work days.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!